|

History of the German 65th Infantry Division

In the summer of 1942, the balance of power

of the forces fighting World War II in Europe remained in German hands.

The United States had still begun bombing operations on the Continent in

earnest. On the Eastern Front, Sevastopol came under siege while German

forces reached the Don River. In North Africa, the port of Tobruk fell

and British forces were sent reeling back to the Egyptian border. The

German Army required new combat formations to control its conquered

territory and continue its fight against stiffening resistance. That

summer the codename "Valkyrie II" heralded the creation of Infanterie

Division 65 (65th Infantry Division).

Formation and Training

The

65th Infantry Division was formed as part of Mobilization Wave 20 in

July 1942 at the training ground at Bitche in Alsace.1 The

division's units were hastily formed and sent to the Antwerp area to

complete their mobilization. Their first combat missions were guard and

security duty at various Scheldt Estuary infrastructure as well as

German military bases. Training was carried out at Maria ter Heide and

artillery ranges at Beverloo and Waterloo. The Allied raid on Dieppe on

19 August 1942 caused a brief interruption to training. Though the 65th

was far away from the action, lessons were nonetheless learned. The use

of Churchill tanks on the main beach by Canadian troops caused a

re-evaluation of anti-tank training among garrison troops in the west.

The raid also reaffirmed Hitler's belief in the need for a strong

Atlantic Wall and the use of fixed fortifications to defend the coast,

rather than the Army's preferred strategy of mobile forces making heavy

counter-attacks. The

65th Infantry Division was formed as part of Mobilization Wave 20 in

July 1942 at the training ground at Bitche in Alsace.1 The

division's units were hastily formed and sent to the Antwerp area to

complete their mobilization. Their first combat missions were guard and

security duty at various Scheldt Estuary infrastructure as well as

German military bases. Training was carried out at Maria ter Heide and

artillery ranges at Beverloo and Waterloo. The Allied raid on Dieppe on

19 August 1942 caused a brief interruption to training. Though the 65th

was far away from the action, lessons were nonetheless learned. The use

of Churchill tanks on the main beach by Canadian troops caused a

re-evaluation of anti-tank training among garrison troops in the west.

The raid also reaffirmed Hitler's belief in the need for a strong

Atlantic Wall and the use of fixed fortifications to defend the coast,

rather than the Army's preferred strategy of mobile forces making heavy

counter-attacks.

Soldiers of the 65th remembered Belgium with

little affection due to poor facilities and inadequate supplies which

even led in some cases to malnourishment.2

Order of Battle: 1942

The 65th Division was organized as a

standard 1939 Type Infantry Division with two infantry regiments and

appropriate supporting arms. It's training and replacement units were

located in Military District 12.

|

65th Infantry Division

Order of Battle - 1942 |

|

Unit |

English Translation |

Notes |

| Infanterie-Regiment 145

|

Infantry Regiment 145 |

3 battalions |

| Infanterie-Regiment 146 |

Infantry Regiment 146 |

3 battalions |

|

Artillerie Regiment 165 |

Artillery

Regiment 165 |

3 light

battalions, 1 heavy battalion |

|

Panzerjäger- und Aufklärungs-Abteilung 165 |

Anti-Tank

and Reconnaissance Battalion 165 |

Combined

anti-tank and reconnaissance |

|

Pionier-Bataillon 165 |

Engineer

Battalion 165 |

Divisional

engineers |

|

Divisions-Nachrichten-Abteilung 165 |

Divisional

Signals Battalion 165 |

|

|

Divisions-Nachschubführer 165 |

Divisional

Supply Unit 165 |

|

|

Sanitätsdienste |

Divisional

Medical Services |

|

The anti-tank and reconnaissance battalion

was reorganized several times. In February 1943 it was renamed

Schnelle-Abteilung 165, and in July 1943 split into two units, an

anti-tank battalion and a reconnaissance battalion. The anti-tank

battalion had two companies, one with towed 3.7cm and 7.5cm guns, and

the other with self-propelled Marder III vehicles.

Occupation Duty

The

65th moved to the Netherlands in October 1942 for occupation duty. The

division spent the next eight months occupying Coastal Defence Sector A1

(Walcheren Island, North Beveland, and South Beveland). The initial

supply of personnel for the 65th had an average age of 30 years, and one

in four already had combat experience. The division sent drafts of men

to rebuild the shattered 44th Infantry Division (Hoch-und-Deutschmeister)

which had suffered at Stalingrad, and in return received large numbers

of recruits from Silesia. Another activity the 65th participated in here

was the creation of coastal fortifications of a wide variety of types,

including bunker, gun casemates, observation positions, and other

concrete constructions as part of the so-called Atlantic Wall. In the

event, most were never used, though Canadian and British forces did

attack Walcheren Island from both east and west two years later, long

after the 65th had left the area. The

65th moved to the Netherlands in October 1942 for occupation duty. The

division spent the next eight months occupying Coastal Defence Sector A1

(Walcheren Island, North Beveland, and South Beveland). The initial

supply of personnel for the 65th had an average age of 30 years, and one

in four already had combat experience. The division sent drafts of men

to rebuild the shattered 44th Infantry Division (Hoch-und-Deutschmeister)

which had suffered at Stalingrad, and in return received large numbers

of recruits from Silesia. Another activity the 65th participated in here

was the creation of coastal fortifications of a wide variety of types,

including bunker, gun casemates, observation positions, and other

concrete constructions as part of the so-called Atlantic Wall. In the

event, most were never used, though Canadian and British forces did

attack Walcheren Island from both east and west two years later, long

after the 65th had left the area.

In October 1942, Infantry Regiments

throughout the German Army were renamed to become Grenadier Regiments, a

cosmetic change meant to invoke the memory of Frederick the Great's

armies and thereby improve morale. In February 1943, Artillery Regiment

165 came under hostile fire for the first time when Allied ships fired

on the port facilities at Vlissingen.

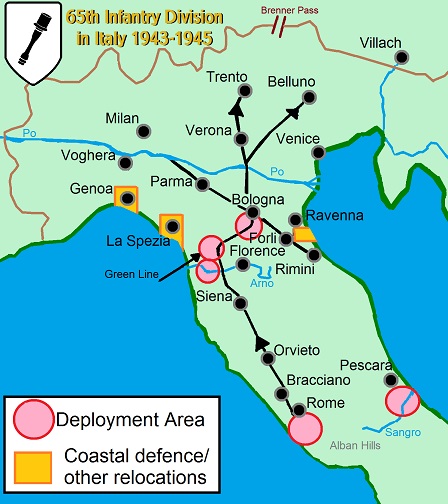

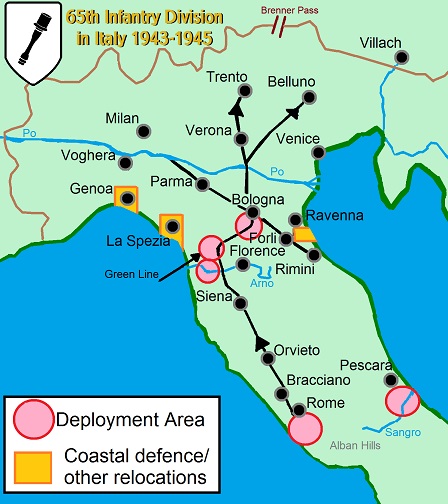

To Italy

The

65th Division moved to France in the spring of 1943. In August 1943 the

division moved briefly to Austria for two weeks before heading south

into Italy just as the fascist government was being overthrown and Italy

changed sides. The division took up coastal defence duties on the

Adriatic from 10 to 22 August 1943 and then relocated to the west coast

at La Spezia in September. Units of the division were on sentry duty

when Italy changed sides, and soldiers watched ships of the Italian Navy

sortie from La Spezia and Genoa, including the battleship Roma. The

65th Division moved to France in the spring of 1943. In August 1943 the

division moved briefly to Austria for two weeks before heading south

into Italy just as the fascist government was being overthrown and Italy

changed sides. The division took up coastal defence duties on the

Adriatic from 10 to 22 August 1943 and then relocated to the west coast

at La Spezia in September. Units of the division were on sentry duty

when Italy changed sides, and soldiers watched ships of the Italian Navy

sortie from La Spezia and Genoa, including the battleship Roma.

In October 1943 the division moved to the Chieti area, and then to the

Adriatic coast between Pescara and Ortona.3

Baptism of Fire: the Sangro River

The 65th Division was ordered to man positions on the Winter Line.

Initially stationed on the coast, the inexperienced division was shifted

inland in favour of the more experienced 1st Parachute Division. The

latter fought at Ortona where it battled the 1st Canadian Division at

Christmastime, 1943 before withdrawing to the Arielli River. The 65th

instead fought at Orsogna, giving ground to the 8th Indian Division and

the 2nd New Zealand Division, but held on to the city of Orsogna before

being relieved. The division had suffered enormous losses, particularly

in infantry.

The division was relieved by the 334th Infantry Division in the last

days of 1943, and relocated to Genoa where it was partly reconstituted.

At the same time the division reorganized as a "Type 1944" Division,

with three infantry regiments (145, 146, 147) of two battalions each

rather than two regiments of three battalions. The reorganization

increased the division's firepower (particularly in terms of anti-tank

guns and infantry howitzers) while conserving manpower - a necessity

brought on by the heavy loss of life on the Eastern Front. The

reconnaissance battalion was gone, replaced by a divisional Füsilier

Battalion which was organized along the lines of the battalions in the

Grenadier Regiments. Each rifle squad in the Grenadier and Füsilier

battalions was reduced from a paper strength of 10 men to 9. The towed

anti-tank company of the divisional anti-tank battalion had its guns

replaced by the StuG M42 (Italian designed assault gun adopted by the

Germans) and in December 1944 these were in turn replaced by the

Jagdpanzer 38 (a German conversion of a Czech-built tank, popularly but

inaccurately known as the Hetzer).

|

65th Infantry Division

Order of Battle - 1944 |

|

Unit |

English Translation |

Notes |

| Divisions-Füsilier-Battalion

65 |

Fusilier Battalion 65 |

Divisional recon, equipped

as Grenadier Battalion |

| Infanterie-Regiment 145

|

Infantry Regiment 145 |

2 battalions |

| Infanterie-Regiment 146 |

Infantry Regiment 146 |

2 battalions |

| Infanterie-Regiment 147 |

Infantry Regiment 147 |

2 battalions |

|

Artillerie Regiment 165 |

Artillery

Regiment 165 |

3 light

battalions, 1 heavy battalion |

|

Panzerjäger-Abteilung 165 |

Anti-Tank

Battalion 165 |

|

|

Pionier-Bataillon 165 |

Engineer

Battalion 165 |

Divisional

engineers |

|

Divisions-Nachrichten-Abteilung 165 |

Divisional

Signals Battalion 165 |

|

|

Divisions-Nachschubführer 165 |

Divisional

Supply Unit 165 |

|

|

Sanitätsdienste |

Divisional

Medical Services |

|

Anzio

The Allied invasion of Anzio caused an emergency call-out of the

division, per "Case Richard" which was a pre-planned response to an

Allied amphibious landing behind German lines. Grenadier Regiment 145

and 147 relocated to the Anzio area, and elements of the division went

into action as "Kampfgruppe Pfeifer." The division fought for the most

part west of the Anziata (the road linking Anzio to the Alban Hills) and

at times had elements of the 4th Parachute Division under command.

Elements of the division helped reduce the British salient at Campoleone

and then participated in Operation Fischfang, the full-scale

counter-offensive aimed at splitting the Anzio beachhead and pushing the

Allies back into the sea. The division suffered heavy casualties due to

Allied artillery and air power, and after Fischfang petered out the two

Grenadier Regiments were withdrawn to rest.

On 20 March 1944 a soldier in the 5th Company, Grenadier Regiment 147

wrote to his wife:

There are now two serious, unsuccessful attacks behind us,

probably a third will follow, and we have a few hours of rest right

now, but today we have been replaced in the firing line and are

living in a cave right behind the front. Some have fallen and are

still lying outside, because we can not reach them. After five days

of uninterrupted action we are dirty, unshaven and tired enough to

fall over. I am the last of my company's squad and platoon leaders,

all the others are dead or wounded.4

Following the failure of Operation Fischfang,

representatives of the combat units at Anzio were summoned to the

Wolfsschanze. A company commander in Grenadier Regiment 145 is quoted in

the divisional history:

From my command post in the front

line a few kilometers north of the East-West road I was ordered to

the Führer's “Wolf’s Lair” headquarters in Rastenburg / East Prussia

for three days. During my travel, various headquarters wanted to

tell me their individual experiences and concerns to pass on. I was

finally received in a suburb of Rome by the supreme commander of the

14th Army, Generaloberst v. Mackensen. From there I went by

Kübelwagen to Florence and then used the leave train to Berlin. At

last a night-delivery train took me to the Führer's headquarters.

There were four of us from the beachhead and I was the

representative of the 65th Infantry Division. You couldn’t believe

what was told to us there! Some new weapons were shown, and

otherwise we were questioned up and down about why the front wasn’t

moving at Nettuno. To everyone we gave the familiar response: Many

dogs are the rabbit's death!5

A unique circumstance occurred in February

1944 when Leutnant Heinrich Wunn participated in actions for which he

was nominated (and ultimately bestowed) the Knight's Cross of the Iron

Cross, while in the same action an enemy soldier was nominated for (and

ultimately bestowed) the Victoria Cross, marking an occasion in which

opposing forces nominated a soldier for their highest bravery award for

the same battle. When the final Allied offensive operations at Anzio

began at the end of May, Wunn found himself in charge of a defensive

position. After beating back five attacks by British infantry and tanks,

the British are reported to have demanded Wunn's surrender. He reported

the exchange to the divisional commander. "After bloody rebuff, enemy

calls for surrender of Strongpoint Wunn. My reply: Götz von Berlichingen!"6

After Anzio

The division saw further action in the fight for Rome, and later fought

at Florence, the Futa Pass and the Battle of Bologna before surrendering

to the Allies near the Po River in April 1945.

The division and its leadership was mentioned during Hitler's daily

situation conference on 18 June 1944:7

H: How are the commanders of these

units?

JODL: The 65th [Infantry] Division is

good and has always been good.

Following the war, all German formations

were analyzed by U.S. Army intelligence through interrogations of German

officers. Ludwig Graf von Ingelheim assessed the 65th Division's

performance as such in 1947:

Established in Holland in 1942, it

remained there until the autumn of 1943. Relocated to the La Spezia

area in September 1943, from October 1943 in the front line.

Division had worked well and was one of the good infantry divisions.8

The U.S. Army's official historian of the

Italian campaign, Martin Blumenson, noted that the 5th Army's wartime

intelligence had a different opinion that may not have been well

founded:

The units of the Fifth Army that had

fought in December were tired and discouraged. There was a tendency

in some quarters to downgrade the German opposition. For example,

one intelligence report made much of the 'remarkable background' of

the divisions in the Tenth Army - the 44th, 94th, and 305th remade

after Stalingrad, the 15th Panzer Grenadier and Hermann Goering

reconstituted after Tunisia, the 3d Panzer Grenadier, renumbered but

the same mediocre 386th, the 29th Panzer Grenadier, a milking of the

345th, the 1st Parachute drawn from the 7th, the 26th Panzer from

the 23d Infantry - 'Only [the] 65[th] is an original

invention, and it may hardly be regarded as a success.' Yet the fact was that the Germans had

fought resourcefully and well.9

Partisan Warfare and Alleged War Crimes

Following the retreat from Rome in June 1944, the division found the

civil population increasingly war-weary and hostile. While relations

with civilians had always been correct, if not warm, even after Italy

defected, the divisional historian noted that a marked change occurred

after the fall of Rome when the division relocated to northern Italy for

recuperation.

One of the strongest partisan bands was discovered on 16 June in the

Roccastrada area with 400 men. The main activity of the partisans was

road closures, bridge destruction, power and phone line sabotage,

abduction of political prisoners from prisons of the Italian militia,

raids on individual motor vehicles, small motor vehicle columns and

messengers. German authorities repeatedly admonished the Italian

population by appeals not to support the partisan gangs. German units

tried to protect themselves by strengthening sentries and patrols and by

restricting the movements of civilians. In addition, security and

hunting patrols were formed on a case-by-case basis and armed parties

were used to attack the gangs. For example, following the demolition of

the bridges at Frosini and Monticiano, the security group Riecher (from

the divisional Füsilier Battalion) secured the sector Rosia - Torniella

against partisan gangs on the road Siena - Grosseto from the 15 to 19

June.10

The 65th Division has been identified as possibly being responsible for

25 separate acts of violence in which Italian civilians were killed.11

Many of the reports lack evidence of specific perpetrators, only noting

that the killings occurred in the 65th Division's area of operations.

The first such incident occurred in relation to the Frosini and

Moniciano bridge destruction when an Italian civilian was tried by

German military tribunal for espionage, found guilty, and a sentence of

death was carried out.12 Many of the alleged murders involved

confirmed members of the Italian resistance movement that sprang up in

northern Italy to oppose the fascist puppet state.

One of the interactions in the divisional

area was the Ronchidoso massacre, Emilia-Romagna, which also included

the 42nd Jäger Division, between 28 and 30 September 1944, when 66

civilians were executed.13 The Atlas of Nazi war crimes in

Italy mentions that it is possible this massacre was actually

perpetrated by SS troops.14

In total, five separate incidents in which

Italian civilians were killed in the 65th Division's area of operations

occurred in June 1944 (18 victims), three in July 1944 (22 victims),

nine in August 1944 (42 victims), eight in September 1944 (125 victims),

and one in October 1944 (2 victims).15 A number of these

interactions were reprisals precipitated by the killing of German

soldiers by partisans, including in one case the execution of a German

prisoner.16

Divisional Commanders

Generalleutnant Ludwig Friederich Hans Bömers

10 July 1942 – 1 January 1943

Hans Bömers, the first commanding general of

the 65th Infantry Division, was commissioned into the artillery before

the First World War. He was decorated as a junior officer on the Western

Front and stayed in the military after the Armistice in November 1918.

He achieved the rank of Oberst by the outbreak of the Second World War

in September 1939, and commanded the 70th Artillery Regiment at the

start of hostilities. He led the 34th Artillery Regiment in the French

Campaign and moved on to senior artillery posts (Arko and Harko).

After serving on the Eastern Front, acheiving the rank of Generalmajor,

he took command of the 65th Infantry Division on its creation in July

1942, a post he held until New Year's Day 1943 when he left for a new

assignment. He ended the war as a Generalleutnant in the Replacement

Army, was held prisoner by the western Allies from May 1945 to mid-1947,

and died at Braubach in 1984 at the age of 90.

Generalleutnant Wilhelm

Johann Georg Rupprecht Generalleutnant Wilhelm

Johann Georg Rupprecht

1 January 1943 – 31 May 1943

Willy Rupprecht was born in March 1890 in

Bavaria and was commissioned into the infantry in October 1910. He

served with distinction in the First World War, after which he served 15

years in the Bavarian Landespolizei. He returned to the German Army in

1935, and commanded the 213th Infantry Regiment in September 1939 as an

Oberst. After commanding the 327th Infantry Regiment he took command of

the 65th Infantry Division for the first five months of 1943. He went on

to command a Luftwaffe Field Division and later the Grafenwöhr training

area with the rank of Generalleutnant. He ended the war with the 7th

Army Corps.

Generalleutnant Gustav Heistermann von Ziehlberg

? 1943 – 1

December 1943

Gustav Heistermann von Ziehlberg joined his

father's battalion of the 1st Pomeranian Grenadier Regiment in August

1914 and served in various officer positions, achieving the rank of

Oberleutnant. He stayed in the military following the war, and in 1939

was a Major of the General Staff. His first combat command was the 48th

Grenadier Regiment, which he joined as an Oberst in January 1943 during

the Demjansk fighting. He moved to the Führer Reserve in April, and in

mid-1943 took command of the 65th Infantry Division. He was wounded

during the division's first major combat actions in December on the

Sangro River, losing an arm to injuries sustained in an air raid. While

he didn't return to the 65th, he remained a divisional commander

following his recovery, leading the 28th Jäger Division from 28 April

1944, with promotion to Generalleutnant on 1 June. He received the

Knight's Cross for leading his division out of an encirclement at Slonim

during the Red Army's offensive against Army Group Centre. After

implication in the Bomb Plot, he underwent two trials in September and

November 1944. Stripped of all honours, titles and rank, he was shot by

firing squad on 2 February 1945 in Berlin.

Generalleutnant Hellmuth Pfeifer Generalleutnant Hellmuth Pfeifer

1 December 1943 – 22 April 1945

Hans-Hellmuth Pfeifer was born in Thuringia on 18 February 1894 and

joined the Imperial Army in 1912, commissioning as an infantry Leutnant

the next year. At the start of the First World War he commanded a

company of the 4th Hanoverian Infantry Regiment and over the course of

two years earned both grades of the Iron Cross. He stayed in the Army

briefly after the war, and left in 1922 to manage a transportation

company. In 1929 he took over a publishing firm as director. In 1934, he

returned to the Army with the rank of Hauptmann, once again becoming a

company commander. In 1937, as a Major, he moved to duties at OKW (Armed

Forces High Command) and remained on staff at OKW when the Second World

War began. By December he had been promoted to Oberstleutnant and placed

in command of the 3rd Battalion, Infantry Regiment 185. In June 1940 he

received the 1939 clasp to both the Iron Cross 2nd Class and 1st Class.

Pfeifer led his battalion through the

campaign in the west, then led the entire regiment into Russia in the

summer of 1941, with promotion to Oberst in October, and award of the

Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross in November. In October 1942 Pfeifer

received the German Cross in Gold. A month later he was wounded, and

recovered from his injuries until July 1943. In September Pfeifer was

promoted to the rank of Generalmajor.

Generalmajor Pfeifer took command of the

65th Infantry Division in December 1943. Aged fifty, he was described in the divisional history as having

"indomitable energy" and of being a "military role model." Unusually for

a General, he wore the Infantry Assault Badge. He changed the

division's tactical insignia from the letter Z to a stylized hand

grenade, insignia which it retained for the rest of the war. Pfeifer was

killed a few days before the surrender of German forces in Italy on 2

May 1945.

Award Recipients

|

Oakleaves to the Knight's Cross of the Iron

Cross

-

Oberst Martin Strahammer, Commander, Grenadier Regiment 146 (11 August

1944)

-

Generalleutnant Helmuth Pfeifer, Commander, 65th Infantry Division (5

September 1944)

Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

-

Leutnant Heinrich Wunn, 7th Company, Grenadier Regiment 147 (11 June

1944)

-

Gefreiter Johann Vetter, 14th (Anti-Tank) Company, Grenadier Regiment

147 (15 June 1944)

-

Oberleutnant Wilhelm Finkbeiner, 14th (Anti-Tank) Company, Grenadier

Regiment 147 (20 July 1944)

Honour Roll Clasp of the German

Army

-

Oberst i.G. Kühl, Commander, Grenadier Regiment 145 (unknown)

-

Unteroffizier Gerhard Kroczewski, 14th (Anti-Tank) Company, Grenadier

Regiment 147 (15 December 1944)

-

Hauptmann Siegfried Kurzweg, Commander, 1st Battalion, Grenadier

Regiment 147 (17 December 1944)

German Cross in Gold

-

Oberleutnant Adalbert Bauer, 6th

Company, Grenadier Regt 145 (13 December 1944)

-

Hauptmann Klaus Behschnitt,

2nd Battalion, Grenadier Regt 146 (27 July 1944)

-

Hauptmann Max Dollhopf, 2nd

Battalion, Grenadier Regt 146 (13 December 1944)

-

Oberfeldwebel Heinrich Fröhlich,

4th Company, Grenadier Regt 145 (16 June 1944)

-

Major Fritz Hereus, Anti-Tank

Battalion 165 (28 April 1944)

-

Major Walter Hudezeck, Pioneer

Battalion 165 (30 December 1944)

-

Oberstleutnant i.G. Klaus von

dem Knesebeck, Ia, 65th Infantry Division, (7 August 1944)

-

Leutnant d.R. Wilhelm Lauterbach

2nd Company, Anti-Tank Battalion 165 (11 May 1944)

-

Feldwebel d.R. Hans Mühlsteff,

2nd Company, Anti-Tank Battalion 165 (6 August 1944)

-

Leutnant d.R Georg Ortner, 1st

Battalion, Grenadier Regt 145 (16 June 1944)

-

Oberleutnant Werner Pankow,

Füsilier Battalion 165 (12 August 1944)

-

Hauptmann Lucian Reinhold, 2nd

Battalion, Grenadier Regt 147 (11 May 1944)

-

Oberst Heinz Sackersdorff,

Commander, Artillery Regiment 165 (26 September 1944)

-

Oberfeldwebel Paul Schimanski,

Grenadier Regiment 145 (13 December 1944)

-

Oberstleutnant Hermann Suffa,

Grenadier Regiment 147 (26 July 1944)

-

Oberleutnant Vinzens Urban, 3rd

Company, Grenadier Regt 146 (14 February 1945)

-

Unteroffizier Karl Weintraud,

7th Company, Grenadier Regt 147 (22 December 1944)

|

onwhite.jpg)

Knight's

Cross of the Iron Cross

Honour

Roll Clasp

(on Iron Cross 2nd Class Ribbon)

German

Cross in Gold |

Notable Soldiers

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau served in the 65th Infantry Division after

being drafted and serving on the Eastern Front. He reportedly sang for

his comrades of Grenadier Regiment 146 at entertainment evenings behind

the lines.17 He was captured by U.S. troops in 1945.18

Divisional Insignia

The division adopted a kugelbaum (Ball Tree) insignia for use on

vehicles, road signs, etc. When General von Ziehlberg took command in

mid-1943, he changed the divisional insignia to the letter 'Z' (the

first letter of his own last name). After von Ziehlberg was seriously

wounded during the fighting on the Sangro River, the division adopted a

hand grenade as its divisional emblem.

|

|

|

| 1942-1943 |

late 1943 |

1944-1945 |

Newsletter

The Divisional newsletter was named Die Handgranate ("The Hand

Grenade"). For Christmas 1944 large quantities of a special holiday

edition were printed with the idea that they should be sent back to

families at home. The edition contained ruminations on the war and a

short report "From the War History of our Infantry Division."19

Citations

-

Velten, Wilhelm. Vom Kugelbaum

zur Handgranate: die Geschichte der 65 Infanterie Division.

Kurt Vowinckel Verlag, Neckargemund, 1974. No ISBN. The town of

Bitche had been turned into a French fortress in the Franco-Prussian

War of 1870. It was ceded to Germany as part of Alsace-Lorraine at

the end of the war. Bitche was ceded back to France in 1918 at the

end of the First World War, and the fortress there was integrated

into the Maginot Line. Alsace was retaken by Germany after the

French Campaign in May 1940.

-

Velten, Ibid

-

Velten, Ibid

-

Velten, Ibid, p.115

-

Velten, Ibid, p.122

-

Velten, Ibid, p.142. The name Götz von

Berlichingen belonged to a medieval count and military commander.

When the writer von Goethe immortalized his life in the form of a

play, his name became a euphemism for the phrase Er kann mich am

Arsch lecken (he can lick my ass).

-

Heiber, Helmut and David M. Glantz

Hitler and his Generals: Military Conferences 1942-1945. (Enigma

Books, New York, NY, 2004) ISBN 1-929631-28-6 p.440

-

"Die personelle und materielle

Lage der deutschen Divisionen in Italien verglichen mit der

Verhältnissen auf allierter Seite" NARA file MS#D-342

-

Blumenson, Martin. US Army in World War

II: Salerno to Cassino. Center of Military History, United States

Army, Washington D.C., 1993.

-

Velten, Ibid, pp.160-161

-

"65. Infanterie-Division" (in Italian).

Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy. Retrieved 20 September

2018.

-

"Villa Montese" (in Italian). Atlas of

Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

-

"Ronchidoso, Gaggio Montano,

28-30.09.1944" (in Italian). Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in

Italy. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

-

"Voci locali, anche se in tono molto

minore rispetto a quelle di Ca' Berna, imputano invece la strage a

truppe SS."

-

Ibid

-

Atlas of the Nazi and Fascist Massacres

in Italy website

-

Velten, Ibid, p. 176.

-

"Lyrical and Powerful Baritone, and the

Master of the Art Song". The New York Times. 18 May 2012.

-

Velten, Ibid, p.179

|

The

65th Infantry Division was formed as part of Mobilization Wave 20 in

July 1942 at the training ground at Bitche in Alsace.1 The

division's units were hastily formed and sent to the Antwerp area to

complete their mobilization. Their first combat missions were guard and

security duty at various Scheldt Estuary infrastructure as well as

German military bases. Training was carried out at Maria ter Heide and

artillery ranges at Beverloo and Waterloo. The Allied raid on Dieppe on

19 August 1942 caused a brief interruption to training. Though the 65th

was far away from the action, lessons were nonetheless learned. The use

of Churchill tanks on the main beach by Canadian troops caused a

re-evaluation of anti-tank training among garrison troops in the west.

The raid also reaffirmed Hitler's belief in the need for a strong

Atlantic Wall and the use of fixed fortifications to defend the coast,

rather than the Army's preferred strategy of mobile forces making heavy

counter-attacks.

The

65th Infantry Division was formed as part of Mobilization Wave 20 in

July 1942 at the training ground at Bitche in Alsace.1 The

division's units were hastily formed and sent to the Antwerp area to

complete their mobilization. Their first combat missions were guard and

security duty at various Scheldt Estuary infrastructure as well as

German military bases. Training was carried out at Maria ter Heide and

artillery ranges at Beverloo and Waterloo. The Allied raid on Dieppe on

19 August 1942 caused a brief interruption to training. Though the 65th

was far away from the action, lessons were nonetheless learned. The use

of Churchill tanks on the main beach by Canadian troops caused a

re-evaluation of anti-tank training among garrison troops in the west.

The raid also reaffirmed Hitler's belief in the need for a strong

Atlantic Wall and the use of fixed fortifications to defend the coast,

rather than the Army's preferred strategy of mobile forces making heavy

counter-attacks. The

65th moved to the Netherlands in October 1942 for occupation duty. The

division spent the next eight months occupying Coastal Defence Sector A1

(Walcheren Island, North Beveland, and South Beveland). The initial

supply of personnel for the 65th had an average age of 30 years, and one

in four already had combat experience. The division sent drafts of men

to rebuild the shattered 44th Infantry Division (Hoch-und-Deutschmeister)

which had suffered at Stalingrad, and in return received large numbers

of recruits from Silesia. Another activity the 65th participated in here

was the creation of coastal fortifications of a wide variety of types,

including bunker, gun casemates, observation positions, and other

concrete constructions as part of the so-called Atlantic Wall. In the

event, most were never used, though Canadian and British forces did

attack Walcheren Island from both east and west two years later, long

after the 65th had left the area.

The

65th moved to the Netherlands in October 1942 for occupation duty. The

division spent the next eight months occupying Coastal Defence Sector A1

(Walcheren Island, North Beveland, and South Beveland). The initial

supply of personnel for the 65th had an average age of 30 years, and one

in four already had combat experience. The division sent drafts of men

to rebuild the shattered 44th Infantry Division (Hoch-und-Deutschmeister)

which had suffered at Stalingrad, and in return received large numbers

of recruits from Silesia. Another activity the 65th participated in here

was the creation of coastal fortifications of a wide variety of types,

including bunker, gun casemates, observation positions, and other

concrete constructions as part of the so-called Atlantic Wall. In the

event, most were never used, though Canadian and British forces did

attack Walcheren Island from both east and west two years later, long

after the 65th had left the area. The

65th Division moved to France in the spring of 1943. In August 1943 the

division moved briefly to Austria for two weeks before heading south

into Italy just as the fascist government was being overthrown and Italy

changed sides. The division took up coastal defence duties on the

Adriatic from 10 to 22 August 1943 and then relocated to the west coast

at La Spezia in September. Units of the division were on sentry duty

when Italy changed sides, and soldiers watched ships of the Italian Navy

sortie from La Spezia and Genoa, including the battleship Roma.

The

65th Division moved to France in the spring of 1943. In August 1943 the

division moved briefly to Austria for two weeks before heading south

into Italy just as the fascist government was being overthrown and Italy

changed sides. The division took up coastal defence duties on the

Adriatic from 10 to 22 August 1943 and then relocated to the west coast

at La Spezia in September. Units of the division were on sentry duty

when Italy changed sides, and soldiers watched ships of the Italian Navy

sortie from La Spezia and Genoa, including the battleship Roma.  Generalleutnant Wilhelm

Johann Georg Rupprecht

Generalleutnant Wilhelm

Johann Georg Rupprecht Generalleutnant Hellmuth Pfeifer

Generalleutnant Hellmuth Pfeiferonwhite.jpg)